Game Literacy

Revisiting August 2007's "Game Literacy", a prescient look at changes in the marketplace that would lead to the explosion of so-called 'Social Games' and the realignment of the market for videogames.

This piece was written for a gaming ‘round table’ back in the Summer of 2007. But it remains eerily relevant today, and looking back at this perspective makes it clear that we were anticipating the seismic shifts that were about to shake up the games industry forever. Zynga’s Farmville was released just two years after this piece was written!

What is the distinction between a Hardcore gamer and a Casual gamer? Are these distinctions still useful to us? Is it valuable to define a third state in between? And what, if anything, can we learn from this terminology?

For many years now, and with origins cloaked in mystery, the crudest audience model has persisted as the one most commonly used – namely the split of players into Hardcore gamers and Casual gamers. It is probably the simple nature of this dichotomy that has allowed it to spread, as humans take to ‘us and them’ distinctions rather too easily. Marcus of Verse Studios suggests that the focus on these terms is entirely misleading, and we should just concentrate on making games that are fun. I admire the sentiment – as long as we remember that one person’s fun can be another person’s horror.

When my company began the research into the gaming audience using survey analysis, we were investigating a particular hypothesis: that those people who constituted the majority of so-called Hardcore gamers belonged to a particular psychological mindset, denoted in Myers-Briggs typology by Introverted, Thinking and Judging [i.e. low Extraversion, low Agreeableness, high Conscientiousness in ‘Big Five]. In effect, we expected Hardcore gamers to be people who kept themselves to themselves, favoured pragmatism over affiliation, and who displayed obsessive-compulsive tendencies.

To conduct the research, we had to decide how to determine if someone could be considered a Hardcore gamer, and to do this we used to methods: firstly self-selection. Players were asked to answer if they considered themselves a Hardcore player, a Casual player or didn’t know. Secondly, we enquired after how much time was spent playing games, and how many different games were purchased and played. As it happened, all of these methods proved to be broadly equivalent: there is significant statistical overlap between players who self-identify as Hardcore (sometimes reluctantly!), players who spend a lot of time each week playing games, and players who buy and play a lot of games. We shouldn’t be entirely surprised!

The hypothesis behind our research was largely disproved. Although it was validated that Hardcore players were more Introverted (in Myers-Briggs terms) than non-Hardcore players, the presumed Thinking and Judging preferences turned out to be indicative of a pattern of play independent of Hardcore status. In fact, Intuitive bias i.e. preference for abstract thinking [Openness to Experience in Big Five] turned out to be a better indicator of Hardcore status. This discovery completely changed the way I thought about the gaming audience, and lead to the development of our research into the many different play styles that exist as an entirely separate issue to Hardcore or Casual status. (More on the subject of this research can be found in our book 21st Century Game Design [now out of print]).

It is important to understand that while this research showed that Hardcore players (both in terms of self-identification, and commitment of time) were predominantly Introverted and Intuitive (in Myers-Briggs terms), neither of these factors are necessarily reliable indicators of a Hardcore player. In particular, there are people who express both traits but have no interest in videogames at all!

So what do we mean when we talk about a ‘Hardcore player?’ Putting aside the subtle and confusing shades that this term has acquired, at heart we mean a player who spends a lot of time playing videogames. I have suggested a better term for such a player is a gamer hobbyist, someone who pursues videogames in the manner of a hobby, rather than as a distraction and diversion. This term is more descriptive than ‘Hardcore’, and comes without the baggage the old term has acquired.

Is a ‘Casual player’ then someone who doesn’t spend much time playing videogames? Well, as it happens there are many players who do not self-identify as ‘Hardcore players’ and who do not buy and play many games but still rack up a lot of hours playing games. They play the same games over and over again (especially games such as Tetris and Solitaire).

If we are to rescue the crude ‘Hardcore versus Casual’ partition and make something more worthwhile of it, we should consider the underlying distinction to be game literacy. By this, I mean the individual’s familiarity with the conventions of videogames, and thus by extension their ability to pick up and play new games with little or no instruction.

It will probably not have escaped notice that videogames evolve along quite channelled lines – that is, genres within videogames show many marked similarities. The potential deviation between one first person shooter and another is vast, yet almost all have a lot in common. The same applies for real time strategy or for almost any well-established genre. This is inevitable: the audience likes to buy games that are similar to the games they have enjoyed in the past (and the games industry, as an employer of gamer hobbyists, likes to make games similar to the games they enjoyed in the past). The inevitable consequence of this dependency is ‘genre conventions’. They may be bent, twisted and and eventually superseded, but each game genre has it’s own habitual tenets, and game literacy represents in part a player’s ability to interpret a new game in the context of their prior experience of these conventions.

The ‘Hardcore gamer’ or gamer hobbyist therefore represents a player with high videogame literacy. Such a player can play any and all games they choose – they have the requisite knowledge to do so – although the actual games they enjoy will vary from person to person. They require little or no tutorial for a game that fits into their existing experience comfortably – perhaps just an explanation of how the conventions of the new game differ from their expectations. A typical gamer hobbyist will have acquired between 15 and 50 player months of experience with videogames, and will also have played 20 to 100 different games in that time. (Note that when I say ‘player month’, I mean a month of continuous play time totalled up).

The ‘Casual gamer’ therefore becomes the player with low or limited gamer literacy. This is an explanation for the simplicity of successful Casual games like Zuma, Bejewelled, Bookworm and Solitaire – to succeed in an audience with low gamer literacy, one must make games that do not require this domain-specific knowledge. Thus a successful Casual game draws from experiences familiar to people from outside of videogames – accuracy (for Zuma), logic puzzles (for Bejewelled), word puzzles (for Bookworm) and card games (for Solitaire). Equally, a successful Casual game requires the player to learn only two or three rules. Thus, the barrier to entry is lowered.

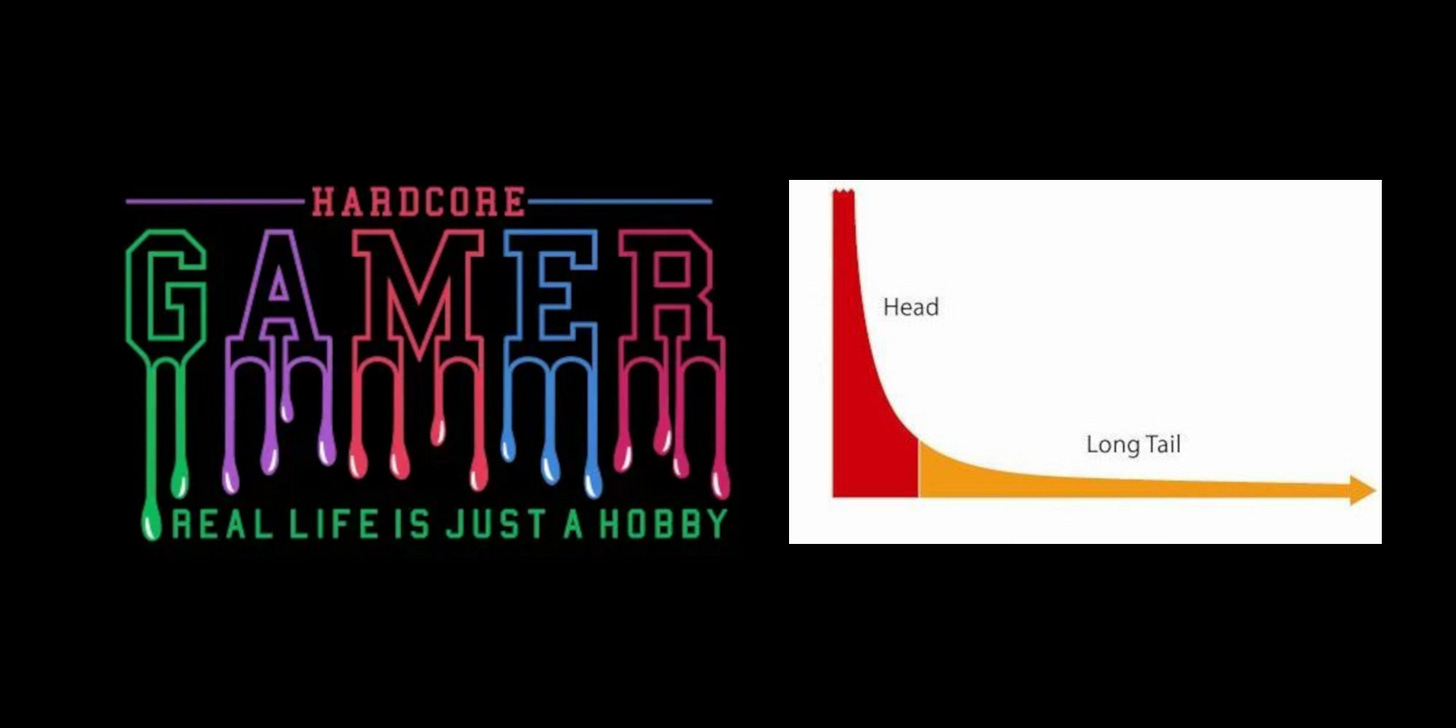

I prefer to term the Casual gamers as the mass market, in keeping with the usual terms used in business. After all, that’s what we’re talking about here: the largest group of consumers, those who lie under the long tail of a particular industry – that’s the mass market, and that’s what I believe we are usually talking about when we talk about Casual gamers.

But of course, what we are talking about here is a continuum: from the spike of the gamer hobbyists, the most game literate, to the tail of the mass market, the least game literate. ‘Hardcore’, as previously used, refers to that spike, and ‘Casual’ refers to the tail.

Of course, being a continuum we can break it up in many different ways. We could split it into three, as Jenova Chen and That Game Company did by defining ‘Core’ as a midpoint or intersection between the two extremes, or we could split it into any other number of segments – say, a sevenfold division into (say) hardcore, hobbyist, experienced, core, inexperienced, casual, mass market – but what would be the point in doing so? We know we are dealing with a continuum, the clearest way to denote such a phenomena is to label the poles (hobbyist and mass market, or Hardcore and Casual) and remember that the majority of people fall between the extremes. That said, render whatever models help you make your games – a model is just a model, after all.

As my company gets ready to launch its next round of research into the gaming audience, the issue of Hardcore versus Casual has slipped into obscurity for us. We will be exploring issues of game literacy instead – although we are still including the self-assessment question from our earlier survey investigation so that we can compare game literacy to self-assessment. But even this is a tangential element of the research we are conducting this time. The survey will go live in two weeks time [back in 2007, that is!], just in time for me to promote it at the Austin Game Developer’s Conference.

Thinking about the issue of ‘Hardcore and Casual’ games in terms of gamer literacy adds clarity to the nature of the situation, and allows us to reason about how to proceed. Those games that used to be the centre of the marketplace are increasingly becoming niche markets for gamer hobbyists, while some – sometimes against all odds – have transitioned to the edge of the mass market (World of Warcraft and GTA being only the two most well known examples).

This gives game designers a choice in how they approach their games: they can target the gamer hobbyist side of the audience, in which case the game either needs to be developed on a prudent budget or be lucky enough to be supported by a platform licensor (Sony, Microsoft, Nintendo) as a possible driver for early adoption or brand loyalty. Or, they can target the ‘long tail’ with simpler games that do not require much if any gamer literacy to play. Or they can work in the space with the greatest potential for both profit and failure – the elusive middle ground between the two extremes. There is success to be found here, but it requires careful consideration of how the games will support players with low game literacy, intelligent structuring, and more than a modicum of luck.

It's probable that the genres beloved by hobbyists can support commercially viable niche markets, and we will see a widening of the gap between such players and the mass market. It is perhaps more likely that the mainstream videogames of the future will need to learn how to balance the needs of the game literate player against the mass market players with little prior gaming experience in order to maintain commercial viability. But the problems to solve in this journey – riddles of difficulty and related issues in game modes to name just two – ensure that the field of game design still has much to learn about how to take videogames forward into the twenty first century.

This is the first of two pieces revisiting ihobo’s thoughts about ‘Hardcore and Casual’ in the late 2000s. The second piece runs in two weeks time.